Memphis

MEMPHIS was a Milan-based collective of young furniture and product designers led by the veteran Ettore Sottsass. After its 1981 debut, Memphis dominated the early 1980s design scene with its post-modernist style.

Jasper Morrison remembers breaking into "a kind of cold sweat" and a "feeling of shock and panic" when he stumbled into the opening of a design exhibition at the Arc ’74 showroom in Milan on 18 September 1981. "It was the weirdest feeling," he recalled years later, "you were in one sense repulsed by the objects, or I was, but also immediately freed by the sort of total rule-breaking."

The rule-breaking had begun in December 1980 when Ettore Sottsass, one of Italy’s architectural grandees, met with a group of younger architects in his apartment on Milan’s Via San Galdino. He was in his 60s and his collaborators - Martine Bedin, Aldo Cibic, Michele De Lucchi, Matteo Thun and Marco Zanini – were in their 20s. With them was the writer, Barbara Radice. They were there to discuss Sottsass’ plans to produce a line of furniture with an old friend, Renzo Brugola, owner of a carpentry workshop.

Originally dubbed The New Design, the project was rechristened Memphis after the Bob Dylan lyric "Stuck Inside of Mobile (With the Memphis Blues Again)" stuck repeatedly at "Memphis Blues Again" on Sottsass’ record player. "Sottsass said: ‘Okay, let’s call it Memphis," wrote Radice, "and everyone thought it was a great name: Blues, Tennessee, rock’n’roll, American suburbs, and then Egypt, the Pharoahs’ capital, the holy city of the god, Ptah."

By February, the group, bolstered by the addition of George Sowden and Nathalie du Pasquier, had completed over a hundred drawings of furniture, lamps and ceramics. There was no set formula. "No-one mentioned forms, colours, styles, decorations," observed Radice. That was the point. After decades of modernist doctrine, Sottsass and his collaborators longed to be liberated from the tyranny of smart, but soulless ‘good taste’ in design.

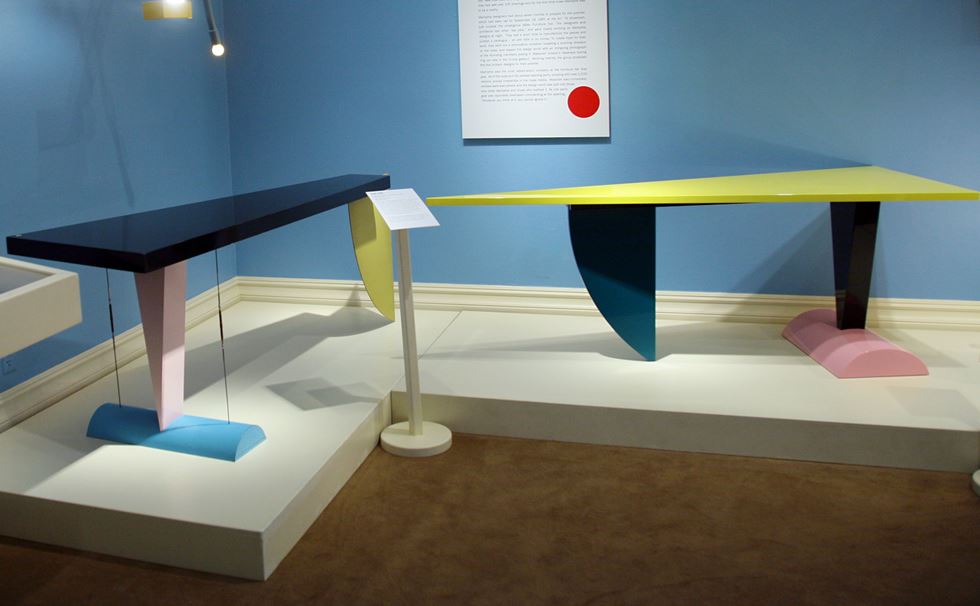

Their solution was to continue the experiments with uncoventional materials, historic forms, kitsch motifs and gaudy colours begun by Studio Alchymia, the radical late 1970s Italian design group to which Sottsass and De Lucchi had belonged. When the young Jasper Morrison and a couple of thousand others crowded into Arc ’74 on 18 September 1981 they discovered furniture made from the flashily coloured plastic laminates emblazoned with kitsch geometric and leopard-skin patterns usually found in 1950s comic books or cheap cafés.

Other pieces of furniture and lights were made from industrial materials – printed glass, celluloids, fireflake finishes, neon tubes and zinc-plated sheet-metals – jazzed up with flamboyant colours and patterns, spangles and glitter. By glorying in the cheesiness of consumer culture, Memphis was "quoting from suburbia," as Sottsass put it. "Memphis is not new, Memphis is everywhere." Matteo Thun described Memphis as "a mental gymnasium".

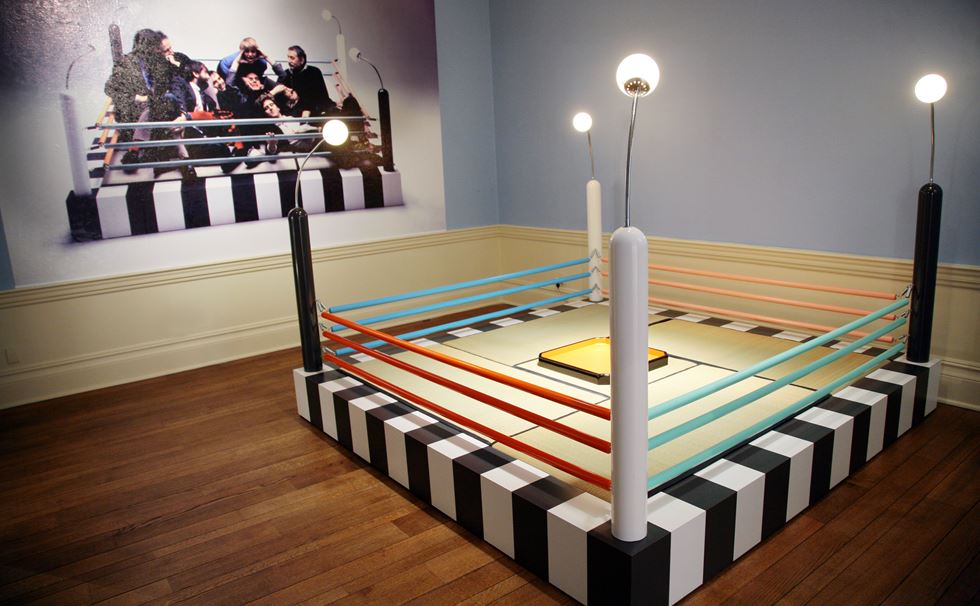

Sottsass’ 1981 Beverly cabinet sported green and yellow ‘snakeskin’ laminate doors with brown ‘tortoiseshell’ book shelves at a topsy turvy angle and a bright red bulb in the light. Sowden’s 1981 Oberoi armchairs combined tomato red upholstery with bright yellow or blue legs and Nathalie du Pasquier’s pink and black mosaic print in a chubby 1950s style. Martine Bedin’s 1981 Superlamp ressembled an illuminated dachsund with multi-coloured bulbs framing a richly-coloured fibreglass arc. Team Memphis posed for a group portrait lounging in Tawaraya, a boxing ring-cum-playpen with a monochrome striped base, pastel-coloured ‘ropes’ and a white light bulb at each corner designed by a Japanese collaborator, Masanori Umeda. The finishing touch was the invitation to the exhibition opening: a postcard image of a yawning dinosaur painted against a lightning-scarred sky by Luciano Paccagnella.

It was an exuberant two-fingered salute to the design establishment after years in which colour and decoration had been taboo. Memphis also scoffed at the notion that ‘good’ design had to last. "It is no coincidence that the people who work for Memphis don’t pursue a metaphysic aesthetic idea or an absolute of any kind, much less eternity," observed Sottsass. "Today everything one does is consumed. It is dedicated to life, not to eternity."

Little about Memphis was truly innovative. Most of its concepts had been trail-blazed by Alchymia. Yet the Memphis collaborators were much more adept at communicating their ideas and at manipulating Ettore Sottsass’ contacts. He even persuaded Artemide, the Italian lighting manufacturer, to work with them.

Within the design world, Memphis was a watershed. "You were either for it, or against it. "All the boring old designers hated it. The rest of us loved it," recalled Bill Moggridge, co-founder of the IDEO industrial design group. Among the old guard was Vico Magistretti. "This furniture offers no possibility of development whatsoever," he declaimed. "It is only a variant of fashion."

Memphis was seen as equally sensational outside the closed confines of the design community. The packed opening party, cool graphics and hip young designers – male and female, from different countries - proved irresistible to the mass media. Perfectly in tune with an era when pop culture was dominated by the post-punk flamboyance of early 1980s new romanticism, Memphis was also a colourful, clearly defined manifestation of the often obscure post-modernist theories then so influential in art and architecture.

Fashion designer, Karl Lagerfeld, furnished his Monte Carlo apartment with Memphis. The US architect, Michael Graves, joined the collective: as did Javier Mariscal from Spain, Arata Isozaki and Shiro Kurumata from Japan. Memphis was splashed across magazines worldwide. There were exhibitions in London, Los Angeles, Tokyo, San Francisco, New York and back in Milan. But Sottsass became increasingly disillusioned with Memphis and the media circus around it, in 1985 he announced that he was leaving the collective.

Like Miles Davis, who resolutely refused to replay old music, throughout his long career, Sottsass always insisted on moving forward rather than reliving past glories. For him, quitting Memphis at the height of its fame was the only logical course of action. "Acclaimed as a symbol and persecuted like a rock star, far from feeling satisfaction or pleasure, he (Sottsass) sank into one of the worst crises of his life," wrote Barbara Radice a few years later.

Having broken free from Memphis, Sottsass concentrated his energies on his own architectural practise, Sottsass Associati, where he continued to work with many of his young collaborators, including Branzi, Cibic and De Lucchi. "I am a designer and I want to design things," Sottsass had written a few years before founding Memphis. "What else would I do? Go fishing?"

All images courtesy of Dennis Zanone