Profile

Luigi Colani

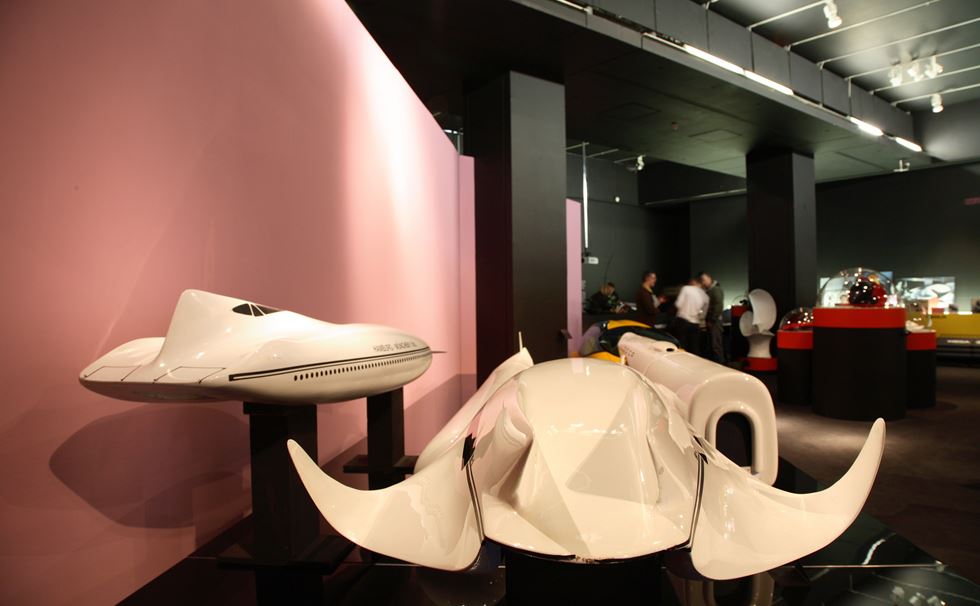

Translating Nature

‘Whenever we talk about ‘biodesign’ we should simply bear in mind just how amazingly superior a spider’s web is to any load-bearing structure man has made. From this insight, we should look to the superiority of nature for the solutions. If we want to tackle a new task in the studio, then it’s best to go outside first and look at what millenia-old answers there may already be to the problem.’

Luigi Colani is one the great mavericks of 20th century design with an independent spirit, a flair for showmanship and a willingness to engage the wider public that has kept him outside the design mainstream.

With a background in car styling and aerodynamics, Colani has pursued an interest in imagining a world that does not yet exist — one of utopian architecture, high performance cars and huge supersonic aircraft flying many times the speed of sound and light.

Born in Berlin in 1928, Colani dropped out of art school and moved to Paris as a 19 year old. He worked as an illustrator in the advertising industry where he produced a series of speculative ideas for cars, motorcycles and aircraft that combined new technology with new materials and which were styled to look ‘modern’ in the bleak context of post-war reconstruction.

Colani worked for a number of car makers and coachwork builders before setting up his own studio in Germany. From his workshop, located in a converted castle near Karlsruhe, his team continue to work in fibre glass to create the shapes and machines that inspire and interest him.

Colani and his team often work on several projects at the same time — an unusual characteristic for a studio within the context of an increasingly commercial design world. Driven by curiosity and experimentation beyond the need to simply satisfy a client, the studio might develop and then abandon a concept for years yet later return to similar themes.

Inspired by natural, organic forms, especially sea creatures, but also by explicit sexual imagery, Colani was an isolated voice during his early career in the 1950s and 1960s in his obsessive search for a design language that goes beyond the mundane functional world. Today the energy and exuberance of his shape making look much more at home in the context of ‘blob’ architecture and the complex curves made possible by digital technologies.

From his earliest projects, ranging from model making for racing teams in Paris and producing DIY kits to customise VW chassis, or more recently building his own trucks in fantastically organic forms, Colani has always looked to subvert mass production. Some creations have made the translation from concept to commercial products such as his SLR T90 camera for Canon and Cobra headphones for Canon. There are also Colani-designed teapots, mineral water bottles and sunglasses in production, but the majority of his inspired work remains in the form of dream-like, organic models or photographic montages.

Image Credits

Translating Nature exhibition, Design Museum, photography by Luke Hayes